The decline of North Sea industry in Scotland has triggered Aberdeen’s economic downturn

In the early 1990s, one ATM on Aberdeen’s grand thoroughfare Union Street boasted the highest value of withdrawals in Europe.

The rollout of cutting-edge offshore technologies following the 1973 energy crisis had attracted major producers to the “oil capital of Europe”, bringing high salaries, soaring property prices and conspicuous consumption.

But Scotland’s third largest city — unlike other fossil fuel hubs — has struggled to recover from the global oil slump of 2014, when prices plummeted 75 per cent over two years to $27 a barrel.

In the decade since, prices have averaged more than $65 a barrel, fuelling renewed growth in boomtowns from Dubai to Houston, which have benefited from revived oil and gas activity in their regions.

Many in Aberdeen argue that successive administrations’ high taxation and insufficient investment allowances, rather than the geology of a declining basin, are to blame.

As the UK Labour government mulls its future energy policy this autumn, Aberdeen’s glory days remain doggedly in the past.

“[Governments] have made it a difficult place to sanction investment — and Aberdeen has seen the consequences,” said businessman Bob Keiller, former chief executive of energy multinational Wood Group, who started out in oil and gas in 1986.

A few years ago, rows of empty shops on the denuded Union Street reflected the city’s wider decline, with a quarter of its 200-odd units unoccupied.

Keiller has since been working to encourage businesses to relocate to the granite-clad city centre, bringing vacancies down from 48 to 23.

Weakness in the historic fossil fuel sector is cascading through the wider north-east economy, where one in six workers is engaged in offshore energy — two-thirds of them in oil and gas.

Aberdeen has lost about 18,000 jobs, or 10 per cent of the workforce, since 2010, largely as a result of the decline in the local oil and gas industry, according to EY.

Industry fears for the future of the city elicit condemnation of the UK government’s move to end new exploratory drilling in the North Sea.

Cutting the “windfall” levy on energy profits and raising investment allowances would allow half of the UK’s oil and gas needs by 2050 to be sourced domestically, oil lobbyists argue, up from current forecasts of less than a third.

Climate activists counter that chasing the final barrels of fossil fuels from the mature North Sea basin would hamper efforts to meet legally-enshrined environmental targets.

“Aberdeen is at the centre of our clean energy mission,” said the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero. “We are delivering a fair and prosperous transition in the North Sea.”

While many Aberdeen executives applaud the “drill, Scotland, drill” mantra espoused by US President Donald Trump, they decry his opposition to wind farms. A premature end to oil and gas extraction would hollow out the domestic supply chain needed for offshore wind, they claim.

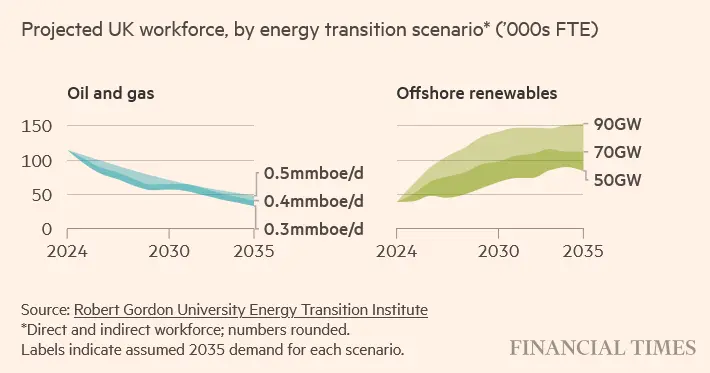

Changes to the composition of the UK energy workforce depend on the speed of the transition from oil and gas to renewable sources

With Scotland’s offshore workforce forecast to fall from 75,000 last year to between 45,000 and 63,000 in the early 2030s, the country needs to “capture a significant share of future renewables activities”, according to a recent report by Robert Gordon University.

The renewables industry in Scotland, which faces challenges such as slow consents and heightened transmission costs, may fail to generate enough employment to replace lost fossil fuel jobs, it warned.

One company at the forefront of the transition is Aberdeen-based North Star. In the past five years, the ship operator has gone from having all of its chartering commitments with the fossil fuel sector, to 70 per cent in renewables, said chief executive Gitte Gard Talmo.

When Talmo, a Norwegian, moved to Scotland last year, she assumed competition for offshore wind business would be “crowded” while oil and gas industry would be doing “very well”. Norway, which generates most of its electricity from hydropower, continues to drill for fossil fuels in the North Sea as it expands its renewables sector.

“Actually, it turned out to be the other way around, due to policy weakening the outlook for the main [oil] operators in Aberdeen,” she said.

The region, which used to top business sentiment surveys, has in recent years slipped down their ranks, said Russell Borthwick of the Aberdeen and Grampian Chamber of Commerce.

“We are now rock bottom on almost every measure,” said Borthwick. “The hand that has fed them for 50 years has stopped feeding.”

Aberdeen’s faltering economy is illustrated by the to-let signs visible on Victorian mansions across the upmarket West End, where some grand corporate offices are being renovated into residences because of lower commercial demand.

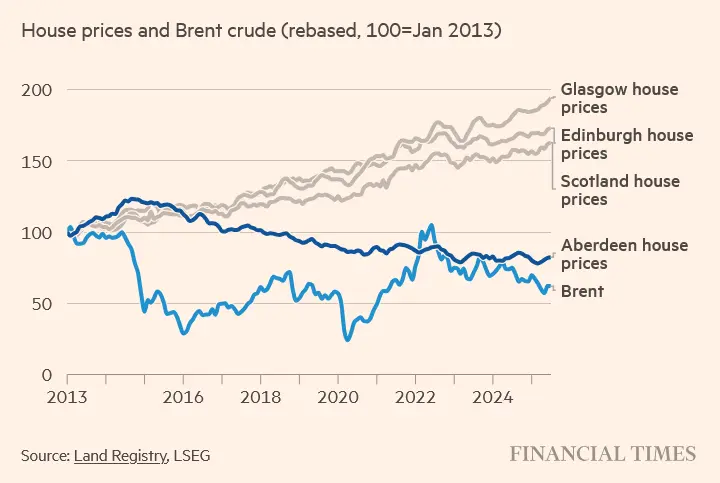

Rivalling London in its 1990s pomp, the city’s property market has long been correlated to oil prices. Growing companies would hoover up graduates as well-paid executives bought up second homes.

Although Aberdeen’s property market recovered faster than other cities following the global financial crisis, it has struggled over the past decade, noted Chris Comfort, partner at Aberdein Considine.

“The delay in investment in renewables is leading to a number of skilled workers moving away,” he said.

Unlike other Scottish cities, average house prices in Aberdeen began a long slide with the fall in Brent crude prices in mid-2014

Nick Dalgarno, of investment bank Piper Sandler, said the trend of staff moving to markets with more favourable tax regimes, especially the oil-rich Gulf, is “most worrying”.

Some companies such as UK-listed Hunting have gone public on plans to grow in the Gulf, while others are quietly expanding their Middle East footprint. The troubled Wood Group has received a takeover offer from Dubai-based Sidara.

“High earners are moving out — that’s not only damaging for Aberdeen, but the UK more broadly,” Dalgarno said. “The exodus could be slowed, but lots need to be done.”

One such worker is Gavin, who had worked in the North Sea subsea sector for 25 years until opportunities started to tail off a few years ago.

Changes to tax arrangements for contractors would have slashed his take home pay just as the introduction of the oil windfall tax in 2022 undermined industry confidence.

With Labour promising to raise the levy further and to end new drilling in the North Sea, he decided to “jump ship” before the general election last year. He joined a maritime firm in Qatar, where five of the 40 staff members hail from the Aberdeen area.

“Oil and gas aren’t dirty words here, like in the UK,” said the 52-year-old engineer, who did not want his surname revealed. “I don’t see any incentive to come home.”

“From our platform to LinkedIn’s energy professionals – your announcements reach the entire sector’s network, not just our readers.”