Neo Next+ follows a whole spate of other similar tie-ups

Some company mergers are grand gestures of bullishness and derring-do. Others are a forlorn attempt to huddle together for warmth in an inhospitable environment. If the battle for US media giant Warner Bros Discovery is the former, then a deal struck on Monday in the North Sea looks decidedly like the latter.

Oil and gas drillers in the chilly expanse to Britain’s east have been buffeted by the country’s Energy Profit Levy — commonly known as the “windfall tax”, even though it still applies when no wind blows. One response has been to seek scale. TotalEnergies on Monday merged its activities into a joint venture with private equity group HitecVision and Spain’s Repsol, which will have more than $15bn of net assets, according to Citigroup analysts.

The creation of this venture, named Neo Next+, follows a whole spate of other North Sea tie-ups. Italy’s Eni and Ithaca joined forces in April 2024. Equinor and Shell did likewise in December last year. Repsol and HitecVision formed their alliance, currently called Neo Next without the plus sign, only a few months ago.

It isn’t hard to see why all these companies have been rushing to team up. Forget deserts and deep seas: the UK is one of the hardest places in the world for energy companies to make money. Assets are mature, costs are high and the tax take has reached 78 per cent of profit.

Mergers help in two main ways: bigger companies can lower unit production costs, and a company’s tax credits from past losses can be offset against more production, so that the benefit flows through sooner. That has certainly been a key attraction in recent tie-ups: Ithaca and Equinor both had substantial tax credits on their balance sheets.

Neo Next+ will benefit from both lower costs and lower taxes. It will produce more than 250,000 barrels of oil a day next year. That makes it 80 per cent larger than its next competitor, Shell and Equinor’s combined business Adura, Citi reckons. And at the end of last year, before their merger, Neo Energy and Repsol together had almost $1bn tax credits, according to Stifel analysis.

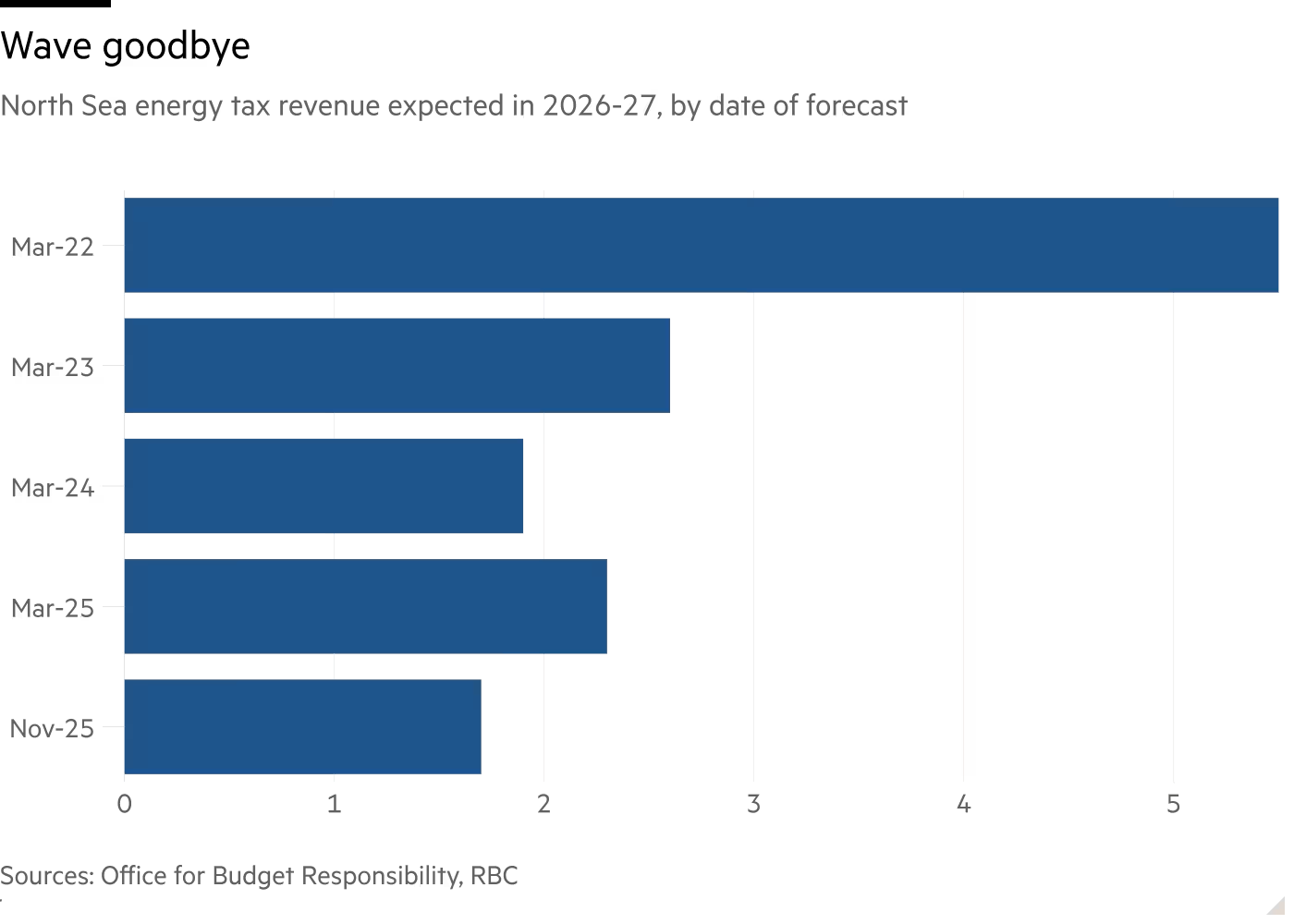

For the UK government, meanwhile, such mergers have both costs and benefits. True, they create sturdier companies that can better withstand the stormy environment, and theoretically taxable profits. But that can be more than offset by the impact of those tax credits. The Office for Budget Responsibility partly blamed mergers for the £2.5bn reduction in its 2025-26 estimate of tax income from the North Sea.

The upshot is that mergers have squeezed the UK’s expected tax receipts from the North Sea at a time of already-declining oil prices and production. All of which does little to inspire love for the windfall tax, especially given the UK’s reliance on energy imports and the jobs the oil and gas sectors create. The levy looks to have been more successful at inspiring mergers than it has at bolstering the country’s finances.

“When you share your news through OGV, you’re not just getting coverage – you’re getting endorsed by the energy sector’s most trusted voice.”